Relevancy and Engagement

www.agintheclass.org

Relevancy and Engagement

www.agintheclass.org

Global Trade and Interdependence

Grade Level

Purpose

Students will examine the impacts of the Columbian Exchange and identify the economic and cultural impacts of contemporary global agricultural trade. They will also explore how food choices influence patterns of food production and consumption. Grades 9-12

Estimated Time

Materials Needed

Engage:

- Food Names That Are Totally Fake podcast (4:30 duration)

- On the Map: Why Some Foods Are Named After Places slide show

Activity 1: Columbian Exchange

- World Fabric Map*, 1 per group of 3–4 students (or a large paper map, see World Map Template provided)

- Where in the World Food Cards*, 1 set of cards per group of 3–4 students (Answer Key)

- The Columbian Exchange: Crash Course World History #23 video (12:00 duration)

- Note: This video makes reference to the spread of syphilis from America to Europe. Teachers should use discretion as to the appropriateness of such a discussion with students. An option is to simply provide a background of the Columbian Exchange without using the video.

- Where in the World Food Cards Answer Key, 1 per student

*The World Fabric Map and Where in the World Food Cards are available for purchase from agclassroomstore.com.

Activity 2: Commodity Chains

- Internet access for each student

- A Behind the Scenes Look at Starbucks Global Supply Chain video

- How the Trade Map is Being Redrawn

Activity 3: Global Trade

Vocabulary

absolute advantage: the ability of a country, individual, company or region to produce a good or service at a lower cost per unit than the cost at which any other entity produces that good or service

agricultural commodity chain: a network of labor and production processes—raw materials, processing/manufacturing, distribution, retailers, consumers—whose end result is a finished commodity

Columbian Exchange: a widespread exchange of animals, plants, culture, human populations, communicable disease, and ideas between the New World (Americas) and the Old World (Africa and Europe)

comparative advantage: a situation in which a country, individual, company, or region can produce a good at a lower opportunity cost (production costs, raw materials, taxes, environmental regulations, farmers’ skills, proximity to market) than a competitor

fair trade: a trading partnership, based on dialogue, transparency and respect, that seeks greater equity in international trade and contributes to sustainable development by offering better trading conditions to, and securing the rights of, marginalized producers and workers (World Fair Trade Organization)

food miles: the distance food is transported from the time of its production until it reaches the consumer

local food: the direct or intermediated marketing of food to consumers that is produced and distributed in a limited geographic area

New World: a term referring to the foods and culture originating in the Americas

Old World: a term referring to the foods and culture originating in Europe, Africa, or Asia

trade route: a logistical network identified as a series of pathways and stoppages used for the commercial transport of cargo

value-added product: a raw commodity that is changed to produce a high-end quality product to meet the tastes and preferences of consumers

Did You Know?

- The top five agricultural commodities in the United States are cattle and calves, corn, soybeans, dairy products, and chickens.9

- Five hundred million small farms worldwide are the source of food for 80% of the population of the developing world.1

- One in three US farm acres exports to foreign markets.1

- US agricultural business exports about 23% of raw farm products.1

- Around $6 million in US agricultural products will be consigned for export to foreign markets, on average, every hour, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.1

Background Agricultural Connections

The United States produces the most abundant, most affordable, and safest food in the world. Additionally, the US farmer is the most productive in the history of the world. This is not to say that farming is without challenges. However, “U.S. agriculture in uniquely positioned to provide for the food and fiber needs of a growing world community.”2

This impactful US position began in 1492 with Columbus arriving in America. He brought unique foods, animals, and even diseases to this new land. Conversely, he took those same items back to Europe with him. For the next 200 years, this Columbian Exchange—the transfer of animals, plants, ideas, and diseases—resulted in extensive global trade and cultural transfers, especially in regards to food. People living in the New World (the Americas) were experiencing food initially only found in the Old World (Europe, Africa, or Asia). Trade routes opened up, providing networks of pathways and stoppages used for the commercial transport of cargo.

Today it is estimated that food travels an average of 1500 food miles from the time of its production until it reaches the consumer. How is this possible? Technology and labor provide the production processes necessary to bring a commodity from farm to table. An agricultural commodity chain includes raw materials, processing and/or manufacturing, distribution, retailers, and consumers. This is often a complex network requiring large numbers of inputs and resources (time, money, technology, human labor).

In regards to their food choices, consumers are making demands for global products, and consequently, an interesting system of global trade routes has been created. For example, China’s imports of agricultural products have surged over the past decade, and the United States is a major supplier. China’s residents have realized rising incomes and consequent changing consumer preferences. “As a result, imports of processed and consumer-oriented products like meats, dairy, wine, and nuts are increasingly showing up in Chinese markets.”3

Additionally, global consumers are seeking value-added products in which raw commodities are changed to produce high-end quality products to meet diverse tastes and preferences. According to the United States Department of Agriculture, these products include changes in the physical state or form of the product (e.g., honey and beeswax products), the production of a product that enhances its value (e.g., organic vegetables), or even growing alternative crops (e.g., heirloom or ethnic fruits). These value-added products provide benefits to farmers in terms of realized financial benefits, but these products also require “…additional investment in equipment, technology, personnel, marketing, operations, etc.”4 Some of these products are part of the local food movement in which consumers are committed to purchasing foods grown within certain distances of consumers’ homes. Although this is currently a popular trend, there is no generally accepted definition of “local” food. In 2008, the U.S. Congress adopted the definition as food produced less than 400 miles from its origin, or within the state. However, consumers often define this term for themselves, considering “local” to mean within an acceptable distance from the foods’ origin—50 miles, 100 miles, within the region, etc.

The global products produced by a particular country are determined by that country’s advantage in commercial agriculture. If a country produces a good or service at a lower cost per unit than the cost at which any other country produces that good or service, the producing country has absolute advantage. Sometimes, a country may not be able to produce a good at the lowest monetary cost, but it can produce a good at a lower opportunity cost with regards to production costs, raw materials, taxes, environmental regulations, farmers’ skills, or proximity to market. In this situation, a country has comparative advantage in producing that good.

In order to make international trade fairer for small-scale producers trying to compete in a global market, the fair trade movement was established in the 1940s. This movement is a philosophy that seeks greater equity in international trade and contributes to sustainable development by offering better trading conditions to, and securing the rights of, marginalized producers and workers. Coffee is the most recognizable fair trade product, but others include tea, chocolate, honey, sugar, and wine.

Engage

- Cue the Food Names That Are Totally Fake podcast to 4:00.

- Ask your students: “Where do your favorite foods come from? Can you tell the origin of a food by its regional name? For example, do Swedish meatballs come from Sweden?”

- Play the podcast (until 8:32). Then, ask students if they can think of any other foods with regional names (give them some examples: London broil, Belgian waffles, Buffalo wings).

- Make a list on the whiteboard and write “yes” if students think these foods are named after their places of origin; write “no” if students think the regional names are not reflective of the foods’ origins.

- Show students the On the Map: Why Some Foods Are Named After Places slide show.

Add the foods shown to the list on the whiteboard, and indicate “yes” or “no” based on the criteria noted above. - Tell students that in this lesson they will explore the origins of foods commonly eaten today and examine agricultural products that are globally traded. Ask them, “Did venetian blinds come from Venice?”

Explore and Explain

Activity 1: Columbian Exchange

- Divide the class into groups of 4–5 students each. Give one World Fabric Map (or World Map Template) and one set of Where in the World Food Cards to each group.

- Instruct students to place each food card on the map in the country or region where they think the food originated (Old World or New World).

- Once students have placed all cards on the map, give them an answer key and instruct them to move the cards to their correct origins.

- Watch The Columbian Exchange: Crash Course World History #23 video. Instruct students to take notes on the positive and negative impacts of the Columbian Exchange. Note: This video makes reference to the spread of syphilis from America to Europe. Teachers should use discretion as to the appropriateness of such a discussion with students. An option is to simply provide a background of the Columbian Exchange without using the video.

- Lead a class discussion and ask students the following questions:

- What foods would students miss most if the Columbian Exchange (and future exploration) had not occurred?

- What positive impacts resulted from the Columbian Exchange?

- What negative impacts resulted from the Columbian Exchange?

- What value-added products do global consumers want today that necessitate global trade?

Activity 2: Commodity Chains

- Show students the video A Behind the Scenes Look at Starbucks Global Supply Chain.

- For homework or in-class research, assign students a commodity chain to research—food, farm, fabric, flower, or forestry product. Instruct them to describe the steps in the commodity’s supply chain, including “production,” “processing,” “distribution,” “retail,” and “consumption” through written descriptions. Also instruct students to identify each step as primary, secondary, or tertiary. Some example commodity chains are listed below; these same examples are included in the Commodity Chain Examples, which can be printed to share with students.

Commodity Chain Examples:- Beef (select “Beef Production” from menu on left side of page)

- Pork (select “Pork Production” from menu on left side of page)

- Coffee

- Sugar cane

- Poultry (select “Poultry Production” from menu on left side of page)

- Tobacco

- Dairy production (select “Dairy Production” from menu on left side of page)

- How Chocolate is Made

- T-shirt

- How it's Made Food

- Instruct students to graphically depict the commodity chain using computer software or hand drawings.

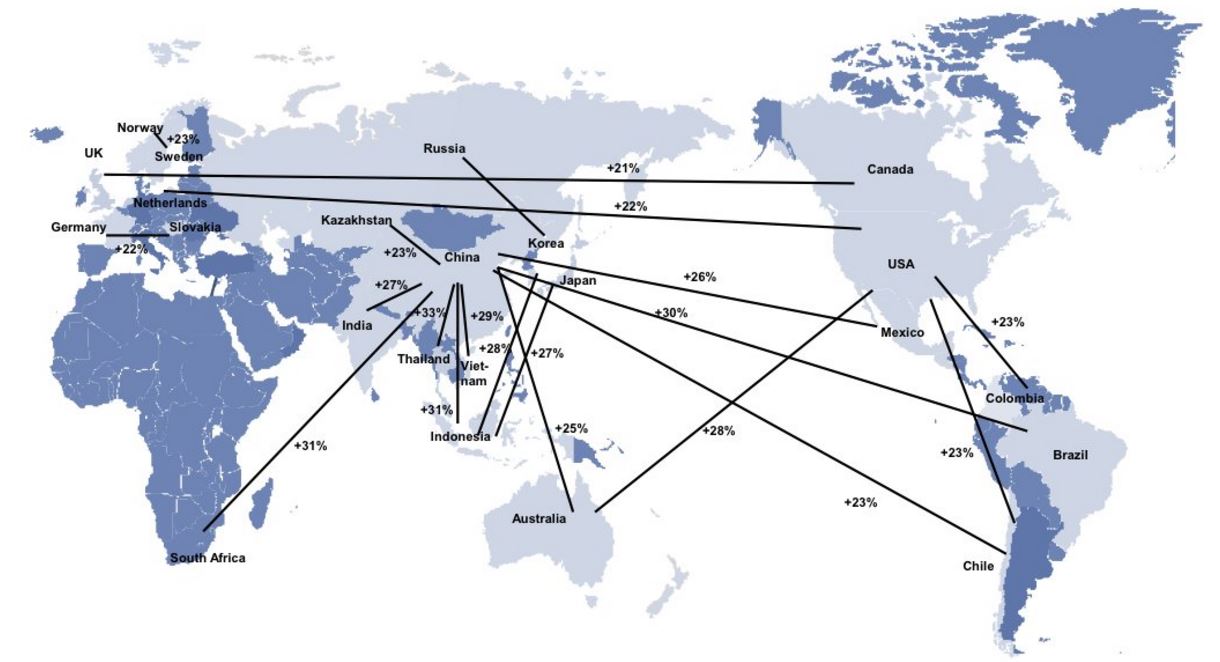

- Display students’ commodity chains in the classroom and/or conduct a class discussion where student share their findings. Show students How the Trade Map is Being Redrawn. Are any of their commodities traded along these routes? If they are uncertain of the answer, have them research this question.

Activity 3: Global Trade

- Use the How the Trade Map is Being Redrawn to assign each student or pairs of students a trade route to research. Following is a list of the routes:

- Norway – Sweden

- United Kingdom – Canada

- Russia – Korea

- Netherlands – United States

- Germany – Slovakia

- Kazakhstan – China

- India – China

- South Africa – China

- Thailand – China

- Indonesia – China

- Vietnam – China

- Indonesia – Japan

- Indonesia – Korea

- Australia – China

- Australia – United States

- Mexico – China

- Brazil – China

- Chile – China

- Chile – United States

- Columbia – United States

- Students will research their trade routes using the following instructions. You can have students take notes and write a summary of their research, or have students draw a map of their assigned routes and graphically depict their research findings.

- Using the website The New Political Economy of Resources, use the arrow button on the bottom of the first page (“More, more and more”) to identify what factors, if any, contribute to the trade of each resource along your assigned route. Note: Hovering the computer mouse over the map provides interactive information on each page of this site.

- Scroll down to the next page, “New interdependencies” and identify any of the interdependencies of resources between your countries.

- Scroll down to the next page, “Policy choices matter.” Are either of your countries affected by this scenario?

- Scroll down to the next page, “Production is concentrated.” Which commodities, if any, are concentrated in your countries?

- Scroll to the page “The next wave of consumers.” What commodities are in demand of the consumers in your countries?”

- Scroll to the page, “Short term flashpoints.” What disruptions might impact the imports/exports of your countries?

- Scroll to the page, “Long term instabilities.” What long term instabilities are impacting your countries?

- Using the website International Trade in Goods, identify the agricultural goods imported and exported between your countries. If data is not available for one of your countries, identify the goods exported by the country with available data.

Elaborate

-

Conduct the Chocolate Taste-Testing activity with your students.

-

Use the websites The Globe of Economic Complexity and/or The Atlas of Economic Complexity for in-depth studies regarding global trade and interdependence. These sites provide excellent data, but they are very complex; the guided “tour” instructions are helpful. You may wish to assign each student or pair of students a research question to investigate using these websites and have students share their research in a report. Alternatively, you may wish to lead a class discussion using these resources.

-

Find additional, related activities in the lesson The Columbian Exchange of Old and New World Foods.

Evaluate

After conducting these activities, review and summarize the following key concepts:

- Production and distribution of food is affected by geography, politics, and economics.

- Geographic location largely determines what plants and animals will grow in a particular region, and as a result distinct diets developed for people living in different parts of the world.

- Today agricultural products are traded globally and often travel thousands of miles from where they were produced to where they are consumed.

- Although agricultural producers may be very distant from consumers, regions of food production and consumption are highly interdependent.

Sources

- https://www.noble.org/globalassets/images/news/legacy/2015/spring/ag-by-the-numbers.pdf

- https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-07/documents/ag_101_agriculture_us_epa_0.pdf

- http://blogs.usda.gov/2015/03/10/china-emerging-as-a-key-market-for-agricultural-products/

- http://www.rd.usda.gov/files/RR221.pdf

- http://fairtradeusa.org/products-partners

- http://fapc.biz/valueadded

- The Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation. (2015, Spring). Legacy, (9)1, pp. 7-8.

- https://afsic.nal.usda.gov/alternative-marketing-and-business-practices/farm-enterprises-and-value-added-products

- https://www.ers.usda.gov/faqs/

Contributors:

Doug Andersen (UT), Nancy Anderson (UT), Paul Gray (AR), Ken Keller (GA), Lisa Sanders (MN), Sharon Shelerud (MN), Allison Smith (UT), Kelly Swanson (MN)

Grace Struiksma, author of the Chocolate Taste-Testing activity and The Columbian Exchange of Old and New World Foods lesson plan

Recommended Companion Resources

- Chocolate Taste-Testing

- Chocolate: How It's Made

- Crop Intensity Maps

- Dirt-to-Dinner: Food Matters

- Mapped: Where Does Our Food Come From?

- Popped Secret: The Mysterious Origin of Corn

- Population, Sustainability, and Malthus: Crash Course World History video

- The Book of Chocolate: The Amazing Story of the World's Favorite Candy

- The Complexities of our Global Food System

- Trading Around the World

- World Fabric Map